Balance Sheet Cleanup - The Hidden Assets Dragging Down Your Valuation

Learn how to identify and address obsolete inventory, uncollectible receivables, and stale prepaids before buyer diligence exposes balance sheet issues

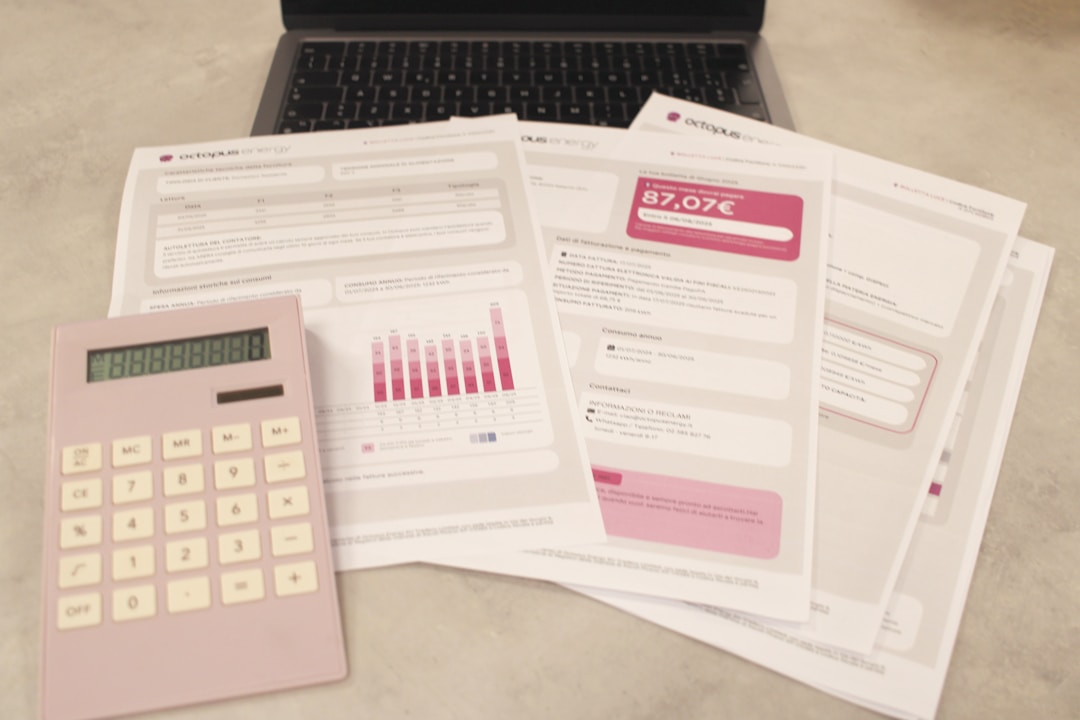

That line item labeled “prepaid expenses” on your balance sheet—say, $47,000 from a software contract you canceled eighteen months ago—tells a sophisticated buyer more about your business than you might think. It whispers of management distraction, suggests financial controls that need tightening, and raises questions about what other surprises might be lurking in your financials. These seemingly small artifacts can quietly erode both your credibility and your proceeds at closing.

Executive Summary

Every business accumulates financial debris over time. Obsolete inventory collects dust in warehouse corners. Receivables from customers who vanished years ago remain on the books. Prepaid expenses for services long discontinued sit untouched. These balance sheet artifacts seem harmless enough during normal operations, until a buyer’s diligence team starts examining your financials with forensic intensity.

Balance sheet cleanup can deliver meaningful returns when material issues exist, primarily because it addresses working capital impact and reduces diligence friction simultaneously. The direct impact shows up in working capital calculations, where inventory and receivable adjustments typically reduce your net proceeds dollar-for-dollar. The indirect impact often matters just as much: clean balance sheets are frequently associated with favorable buyer perceptions, though factors like growth trajectory and market position remain the primary drivers of buyer interest and deal success.

The good news is that balance sheet rationalization follows a straightforward framework. Most cleanup activities require accounting entries, honest assessment, and proper documentation, though the process takes longer than many owners expect, typically 12-20 weeks for a mid-market business when accounting for physical inventory verification, receivable collection efforts, and management coordination. Yet owners consistently delay this work, often because writing off assets feels like admitting failure. This article provides a systematic framework for identifying problem areas, understanding how buyers typically analyze your asset quality, and executing cleanup activities that preserve credibility while optimizing your exit position. We focus primarily on businesses in the $5-50M revenue range, where these issues most commonly affect transaction outcomes.

Introduction

We have observed that balance sheet issues frequently emerge during buyer diligence, particularly in manufacturing, distribution, and service businesses with material inventory and receivables. In our experience working with mid-market transactions, working capital adjustments related to asset quality issues have varied significantly—from under $100,000 to several hundred thousand dollars, depending on the severity of accumulated problems, deal structure, and buyer diligence rigor.

The write-downs themselves hurt, of course. When a buyer determines that a material portion of your inventory is obsolete and adjusts working capital accordingly, that amount reduces your proceeds at closing. But the real damage often comes from what those discoveries imply. Buyers start wondering what else they’re missing. Diligence timelines extend. Additional information requests multiply. The overall deal momentum slows as trust erodes.

Balance sheet cleanup addresses these risks proactively. By identifying and resolving problematic assets before you enter a transaction, you accomplish several objectives. You eliminate the direct financial impact by taking write-downs on your timeline rather than the buyer’s. You demonstrate the management attention and financial discipline that sophisticated buyers value. And you remove potential stumbling blocks before they become negotiating points, though cleanup doesn’t necessarily accelerate the diligence timeline itself, which is determined by the buyer’s process and resource allocation.

This isn’t about hiding problems or making your business appear healthier than it is. Sophisticated buyers will typically identify material issues, though resource and time constraints mean some problems may be missed. Instead, balance sheet cleanup is about presenting an accurate picture of your business, one that reflects current reality rather than accumulated historical artifacts. It’s about having explanations ready before questions arise. And it’s about controlling the narrative around your financials rather than ceding that control to a buyer’s accountants.

One critical caveat: balance sheet cleanup is a necessary preparation step but not a determinant of deal success. Buyers care primarily about growth trajectory, profitability, customer retention, and strategic fit. A clean balance sheet removes friction and prevents late-stage surprises, but it won’t overcome fundamental business challenges. Don’t delay addressing core business issues while perfecting your balance sheet—the time and resources invested in cleanup are wasted if the underlying business isn’t ready for market.

The Anatomy of Balance Sheet Decay

Balance sheets deteriorate gradually, through accumulated decisions that made sense individually but created problems collectively. Understanding how this happens helps you recognize the patterns in your own financials.

How Good Assets Go Bad

Every problematic balance sheet item started as a legitimate business decision. You purchased inventory to meet anticipated demand, demand that never materialized. You extended credit to a customer who seemed creditworthy, until they weren’t. You prepaid for services that would save money over time, until you switched vendors or changed direction.

The decay process accelerates because writing off assets requires active decisions, while keeping them requires only inaction. Your controller might mention that certain inventory hasn’t moved in eighteen months, but addressing it means booking a loss, explaining the write-down to stakeholders, and acknowledging that the original purchase was a mistake. It’s easier to defer the decision. Perhaps the inventory will sell eventually. Perhaps the customer will pay. Perhaps you’ll use those prepaid services somehow.

This deferral mentality creates balance sheets that increasingly diverge from economic reality. The gap might not matter for internal management purposes—you know which assets are real and which are aspirational. But buyers don’t have that context. They see book values and ask what those values mean.

How Buyers Typically Evaluate Balance Sheets

Quality buyers approach balance sheet analysis with healthy skepticism and practiced methodology. They’ve seen enough transactions to know where problems typically hide, and they’ve developed analytical frameworks for testing asset quality systematically.

When a private equity buyer or experienced strategic acquirer reviews your balance sheet, they’re typically asking specific questions about each major category. For inventory, expect requests for aging analysis, turnover metrics, and often physical verification. For receivables, they commonly examine aging buckets, concentration, and historical collection patterns. For prepaids, they usually confirm that future benefit actually exists. For fixed assets, they often test whether assets still operate and contribute to operations.

This analysis goes beyond checking numbers against supporting documentation. In our experience, buyers often evaluate management attention and operational discipline alongside the numbers themselves. A balance sheet cluttered with stale assets may suggest a management team focused elsewhere—on sales growth, perhaps, or product development—while allowing financial housekeeping to slide. That perception creates additional scrutiny, though other factors including growth trajectory, customer diversification, and management team strength typically carry more weight in the buyer’s overall assessment.

Financial buyers (PE firms, investment groups) and strategic buyers (competitors, complementary businesses) often weight balance sheet quality differently. Financial buyers typically scrutinize working capital heavily because adjustments flow directly to their purchase price and affect deal financing. Strategic buyers may care less about certain items if they’ll be absorbed into the buyer’s operations. Understanding your likely buyer type should inform how you prioritize cleanup efforts.

The Big Four Problem Areas

While balance sheet issues can appear anywhere, four categories account for the vast majority of cleanup opportunities. Each requires specific analytical approaches and cleanup strategies.

Obsolete and Slow-Moving Inventory

Inventory problems represent the most common balance sheet cleanup opportunity, particularly for product-based businesses. The fundamental challenge is that inventory costing follows accounting rules that may not reflect economic reality.

Standard inventory costing methods—FIFO, LIFO, or average cost—track what you paid for items, not what those items are currently worth. An item purchased three years ago at $50 might be completely unsaleable today due to obsolescence, damage, or market changes. But it sits on your balance sheet at $50, contributing to an inflated asset total that savvy buyers will challenge.

The cleanup framework for inventory starts with rigorous aging analysis. Segment your inventory by last movement date, not purchase date. For most businesses with typical inventory turns, items that haven’t moved in twelve months deserve scrutiny, and items that haven’t moved in twenty-four months usually require write-down consideration. Industries with inherently longer inventory cycles—capital equipment, custom manufacturing, seasonal goods, and specialty products—require different analysis. A capital equipment manufacturer might carry components for years as standard practice; evaluate these against actual demand patterns and customer order history rather than arbitrary time thresholds.

Beyond aging, examine inventory in the context of current demand. If you’re carrying five years of supply for a slow-moving component, the excess represents capital locked in assets that may never generate revenue. Buyers typically discount this inventory heavily, often to liquidation value or zero.

The cleanup action is straightforward conceptually, if painful emotionally: book reserves against inventory that won’t sell at full value. Work with your accountant to establish reasonable reserve percentages based on aging bands and product categories. Then take the write-down, clean up your balance sheet, and remove the issue from future diligence discussions.

Here’s why this matters for your proceeds: inventory adjustments are almost always included in working capital calculations in purchase agreements. If your balance sheet shows $150,000 in inventory that’s actually worthless, that asset inflates your closing net working capital. The buyer adjusts your proceeds downward by that amount in the working capital settlement. Proactive write-down removes the asset from the closing calculation, preserving your proceeds.

Uncollectible Receivables

Accounts receivable requires similar analytical rigor with different methodology. The question isn’t whether items have moved but whether they’ll ever be collected.

Standard receivable aging shows how long invoices have been outstanding. But simple aging doesn’t capture the full picture. A ninety-day-old invoice from a longtime customer who always pays eventually is different from a ninety-day-old invoice from a customer who’s stopped responding to collection calls. The former will likely become cash; the latter is probably worthless.

Effective receivable cleanup requires account-by-account evaluation for any material balance past due. What’s the customer’s current situation? Have they communicated about payment timing? Is there a dispute underlying the delay? Do they have the financial capacity to pay?

This evaluation often reveals receivables that should have been written off long ago. The customer went bankrupt two years back. The disputed invoice was never going to be collected. The service was never delivered. These amounts sitting in your receivables total represent fiction, not future cash.

Buyers will identify these problems quickly. Their diligence typically includes detailed receivable aging, often with account-level inquiry for material balances. Expect them to ask about your collection process, historical bad debt experience, and current reserve methodology. Inadequate reserves become working capital adjustments, reducing your proceeds.

Specific timeframes matter here: receivables more than 90 days past due with no payment promise warrant aggressive collection or reserve evaluation. Those over 180 days past due are rarely collectible and should be reserved or written off in most industries.

The cleanup approach parallels inventory: establish appropriate reserves based on aging, customer quality, and collection probability. Be aggressive in evaluating collectibility—it’s better to reserve an account that ultimately pays than to carry uncollectible balances that undermine your credibility. Like inventory, receivable adjustments typically affect proceeds dollar-for-dollar in most deal structures.

Stale Prepaids and Deposits

Prepaid expenses and deposits often escape attention because they’re not operational assets. Nobody manages prepaid insurance the way they manage inventory or receivables. These balances sit on the balance sheet, rolling forward period after period, until someone asks what they represent.

The most common issues in this category involve:

Canceled or Changed Services: You prepaid for a multi-year software license, then switched to a different vendor. The unused portion sits in prepaids even though no future benefit exists.

Deposits Never Recovered: You posted security deposits for equipment leases that ended years ago. The deposits were never returned or applied, and nobody followed up.

Expired Contracts: Insurance prepaid for coverage periods long past. Maintenance agreements that weren’t renewed. Subscriptions that lapsed.

Misclassified Items: Amounts recorded as prepaid that were actually expenses, never properly recognized.

The cleanup process here requires a line-by-line review of prepaid balances, asking for each one: what future benefit does this represent, and can we document that benefit? Items failing this test need expense recognition or write-off. Prepaid expenses for services no longer in use should be written off immediately, not deferred.

Prepaid and deposit adjustments primarily improve balance sheet presentation and buyer confidence, but they may not directly affect your purchase price. Unlike inventory and receivables, prepaids are often excluded from working capital calculations in purchase agreements. Discuss with your M&A advisor which specific balance sheet items are included in your deal’s working capital calculation to understand where cleanup effort most directly preserves proceeds.

Questionable Fixed Assets

Property, plant, and equipment balances can harbor issues that affect both valuation and credibility. The most common problems include:

Fully Depreciated but Still Carried: Assets with zero book value that remain on depreciation schedules, cluttering reports without reflecting value.

Disposed but Not Removed: Equipment sold, scrapped, or abandoned that was never removed from the books.

Impaired but Not Written Down: Assets still carried at historical cost despite significant decline in utility or value.

Ghost Assets: Items on the books that cannot be physically located or verified.

Fixed asset cleanup starts with physical inventory—literally walking through your facilities and reconciling what exists against what your records show. Discrepancies require investigation and adjustment. This process often reveals that depreciation schedules include items disposed years earlier, sometimes representing material amounts that should have been removed.

Like prepaids, fixed asset adjustments primarily affect balance sheet ratios and buyer credibility rather than working capital calculations. Significant discrepancies between book records and physical reality create diligence concerns that can affect deal terms beyond working capital.

Understanding Working Capital Mechanics

Before diving into the cleanup framework, you must understand how balance sheet issues actually affect your proceeds. This understanding should drive your prioritization.

In a typical transaction, net working capital (current assets minus current liabilities) is calculated at closing and compared to a target established in the purchase agreement. If your closing NWC exceeds the target, you receive additional proceeds; if it falls short, your proceeds decrease.

Here’s the critical insight: not all balance sheet items affect this calculation equally.

Direct dollar-for-dollar impact (typically included in NWC):

- Inventory and inventory reserves

- Accounts receivable and bad debt reserves

- Most current operating assets and liabilities

Indirect impact on credibility and deal terms (often excluded from NWC):

- Prepaid expenses in many deal structures

- Fixed assets and accumulated depreciation

- Security deposits and long-term prepaids

The specific definitions vary by transaction. Some deals use a broad NWC definition; others use a narrow operating capital calculation. Earnout provisions and escrow structures can shift additional risk post-close. Before you prioritize cleanup efforts, discuss with your M&A advisor which items will actually flow through your deal’s working capital mechanism.

This understanding prevents a common disappointment: an owner cleans up $200,000 across multiple categories, expects to preserve $200,000 in proceeds, then discovers that only $120,000 of those items were included in the working capital calculation. The other cleanup still improved the balance sheet presentation and likely strengthened credibility, but the financial impact was different than expected.

The Cleanup Framework in Action

Effective balance sheet cleanup follows a systematic process that prioritizes impact while ensuring thoroughness. Based on our experience with mid-market businesses, this process typically requires 12-20 weeks for thorough completion, though timelines vary based on several factors: the complexity of your inventory (multiple locations, specialized products), accounting staff availability and capability, and management bandwidth during the cleanup period. Businesses with limited internal accounting resources or significant organizational resistance to write-offs may require 24 weeks or more.

Phase One: Assessment and Quantification

Begin with a complete balance sheet review, examining each material line item through a buyer’s lens. For each category, ask:

- What documentation supports this balance?

- What is the economic value versus book value?

- How would a skeptical buyer evaluate this item?

- What questions would diligence teams likely ask?

Quantify potential issues by estimating write-down amounts for each problem area. This creates a prioritized cleanup list based on financial impact. An obsolete inventory issue affecting $300,000 deserves more immediate attention than a stale prepaid of $15,000, though both need resolution. Focus first on items included in working capital calculations, where cleanup directly preserves proceeds.

Phase Two: Documentation and Support

Before taking cleanup adjustments, ensure you have documentation supporting your conclusions. This matters because buyers will ask about significant adjustments in recent periods. “We wrote off $150,000 of inventory” invites the question “why?” You need clear answers.

For inventory write-downs, document the aging analysis, the physical verification, and the business rationale for obsolescence determinations. For receivable reserves, document collection efforts, customer communications, and creditworthiness assessments. For prepaid adjustments, document the contracts, the terminations, and the absence of future benefit.

This documentation serves dual purposes. It supports your accounting treatment if questioned by auditors or in diligence. It also demonstrates the management attention and systematic thinking that quality buyers value.

Phase Three: Execution and Timing

The mechanical execution of cleanup entries is straightforward—your accountant handles the debits and credits. The timing question requires more thought.

Taking cleanup write-downs 12-24 months before your anticipated sale is often optimal—it provides distance from the transaction while ensuring your trailing financials reflect accurate asset values. Several considerations should adjust this general guideline:

- If you don’t expect a transaction in that timeframe: Conduct cleanup immediately when issues are identified. There’s no benefit to carrying inaccurate balances.

- If a buyer has already appeared: Discuss timing with your M&A advisor. Last-minute cleanup can appear transaction-motivated and may actually create more questions than it answers.

- If your balance sheet is already relatively clean: Don’t create artificial work. Focus instead on prevention processes.

The key principle is avoiding large, unexplained adjustments in the final months before closing, when they appear most suspicious.

Navigating Organizational Friction

While accounting entries are mechanically simple, the organizational friction around cleanup can be significant and represents a common implementation challenge. You’ll need to explain to your team why certain assets are being written off. Prepare narratives about why those assets didn’t pan out—market changes, vendor changes, strategic pivots—that acknowledge reality without implying broader operational incompetence.

If you have external investors or a board, brief them proactively rather than surprising them with write-downs at close. Material write-offs can trigger stakeholder concerns, particularly if they affect lending covenants or investor reporting. Plan for these conversations early, and consider phased implementation if the total adjustment might create alarm. This internal alignment prevents cleanup from becoming an organizational bottleneck. It also gives you practice explaining these decisions, which will serve you well when buyers ask similar questions.

Common Implementation Risks to Anticipate:

Cleanup efforts can uncover deeper operational issues beyond the balance sheet items themselves. If your review reveals systematic control weaknesses—consistent misclassifications, lack of physical verification processes, or inadequate approval procedures—buyers will identify these as well. You may need to extend your timeline and budget to address root causes, not just symptoms.

Building Prevention Into Operations

Cleanup activities address historical accumulation. Prevention ensures you don’t rebuild the problems you’re solving.

Implement regular review processes for each problem category. Review frequencies should match your business size, complexity, and transaction volume. For reference, here are starter frequencies for a typical mid-market business—adjust based on your specific situation:

| Asset Category | Review Frequency | Key Metrics | Action Triggers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inventory | Monthly | Aging by SKU, turnover ratios | No movement in 6+ months triggers reserve evaluation; if no movement resumes within 30 days, establish reserve |

| Receivables | Weekly | Aging buckets, DSO trends | 60+ days past due triggers collection escalation; 90+ days triggers reserve evaluation |

| Prepaids | Quarterly | Balance by vendor, remaining term | Contract changes or cancellations trigger immediate review and write-off of unused amounts |

| Fixed Assets | Annually | Physical verification, utilization | Disposals, replacements, or relocations trigger immediate reconciliation to records |

These processes don’t require significant time or resources once established. They simply institutionalize the attention that prevents balance sheet decay.

Considering Your Alternatives and True Costs

Proactive cleanup is optimal in many cases, but it’s not always the best use of resources. Consider alternatives depending on your situation:

If you already have a buyer engaged: Discuss their specific diligence priorities and balance sheet concerns. Sometimes structuring appropriate working capital adjustments and reserves directly in the deal is more efficient than independent cleanup. The buyer will want to see documentation regardless, so preparation still matters.

If balance sheet issues are small relative to business value: Consider whether your time is better spent on EBITDA growth, customer diversification, or other value drivers. A buyer typically cares more about growth trajectory than historical balance sheet perfection. For a $15M revenue business, cleaning up $50,000 in questionable assets may not be the highest-return activity.

If cleanup effort would be substantial and sale timing is uncertain: Implement prevention processes immediately and defer deep cleanup until 6-9 months before a buyer appears. This preserves optionality without investing heavily in preparation for a transaction that may be years away.

Understanding the True Cost of Cleanup

Many owners underestimate the total investment required for thorough balance sheet cleanup. A realistic cost accounting should include:

Direct Costs:

- Accounting and advisory fees: $5,000-$25,000 depending on complexity

- Physical inventory costs (staff overtime, external verification): $5,000-$25,000 for multi-location businesses

- Collection agency fees for aged receivables: $2,000-$10,000 if external help needed

Indirect Costs (Often Overlooked):

- Executive and management time: 80-150 hours at opportunity cost values

- Accounting staff time: 60-100 hours for thorough review

- Opportunity cost of delayed growth activities during cleanup period

Total Realistic Investment: For a mid-market business with meaningful balance sheet issues, total costs including management time and opportunity costs typically range from $30,000-$100,000 when all factors are considered. This is substantially higher than the direct advisory fees alone.

The Cost-Benefit Analysis

Whether cleanup is worthwhile depends on your specific situation:

Factors favoring proactive cleanup:

- Material issues (over $100,000 in questionable assets)

- Items included in working capital calculations

- Transaction expected within 24 months

- Issues that might raise broader credibility concerns

Factors favoring alternative approaches:

- Small issues relative to enterprise value

- Buyer already engaged and willing to structure adjustments

- Limited accounting resources available

- Transaction timing highly uncertain

When buyers discover material issues during diligence, the impact often exceeds the face value of the problems. The additional scrutiny, extended timeline, and erosion of trust can affect negotiating positions on other terms. The extent of this “credibility discount” varies significantly by buyer, deal size, and overall transaction dynamics—we’ve seen it range from minimal additional impact to meaningful leverage shifts depending on circumstances.

Actionable Takeaways

Start with a buyer’s-eye assessment. Review your balance sheet as a skeptical acquirer would, questioning every material balance and asking what documentation supports reported values. This exercise alone often reveals issues you’ve normalized but buyers will challenge.

Understand which items affect proceeds. Before prioritizing cleanup, confirm with your M&A advisor which balance sheet items are included in working capital calculations for your likely deal structure. Inventory and receivable adjustments typically affect proceeds dollar-for-dollar. Prepaid and fixed asset adjustments primarily improve balance sheet presentation and buyer confidence.

Prioritize by impact and visibility. Focus cleanup efforts on issues that combine material dollar amounts with direct working capital impact. Inventory and receivables typically top this list, as they directly affect working capital calculations and are heavily analyzed in every transaction.

Document everything. Every cleanup adjustment should have clear supporting documentation explaining what was adjusted, why, and how the determination was made. This documentation demonstrates process and protects against diligence inquiries.

Time your cleanup thoughtfully. Aim to complete major cleanup activities before you’re actively engaged with buyers. Twelve to twenty-four months before anticipated transaction is often optimal, but adjust based on your specific circumstances and buyer timeline.

Allocate realistic time and budget. Budget 12-20 weeks for thorough balance sheet cleanup in a mid-market business, with longer timelines for complex inventory or limited accounting resources. Account for the full cost including management time and opportunity costs, which may be several times higher than direct advisory fees.

Anticipate organizational friction. Brief stakeholders proactively, prepare narratives for write-off explanations, and plan for the possibility that cleanup reveals deeper operational issues requiring additional attention.

Build prevention into ongoing operations. Implement regular review processes for each asset category prone to accumulation. Monthly inventory aging reviews, weekly receivable monitoring, and quarterly prepaid reconciliations prevent future buildup.

Conclusion

Balance sheet cleanup isn’t glamorous work. It doesn’t generate revenue, attract customers, or develop new products. It requires confronting accumulated decisions, acknowledging assets that didn’t pan out, and taking write-downs that reduce reported equity. No wonder most business owners defer this work until circumstances force action.

But the circumstances that force action—typically a buyer’s diligence team identifying issues—are exactly the wrong time to address balance sheet quality. By then, you’ve lost control of the narrative. You’re explaining why you didn’t notice problems earlier. You’re negotiating from a position weakened by the implication that other surprises might be lurking. And issues found by buyers become negotiating leverage, often resulting in purchase price reductions and additional scrutiny of other transaction terms.

The owners who optimize their exit outcomes approach balance sheet rationalization as the preparation activity it is—important for removing friction, but not a substitute for fundamental business quality. They clean up proactively, on their timeline, with their explanations prepared. They present buyers with financials that accurately reflect current reality rather than accumulated historical artifacts. And they maintain perspective: a clean balance sheet supports a successful transaction, but growth, profitability, and customer retention remain the primary drivers of buyer interest and valuation.

The work requires honest assessment, systematic review, proper documentation, and realistic time and resource allocation. The returns—in preserved working capital, reduced diligence friction, and strengthened credibility—reward the effort for businesses with material balance sheet issues preparing for exit. Your balance sheet tells a story about your business. Make sure it’s telling the story you want buyers to hear.