When to Walk Away - The Hardest Decision in Selling Your Business

Learn when walking away from a bad deal makes sense using practical frameworks to evaluate terms and make rational decisions under transaction pressure

You’ve spent six months in due diligence. Legal fees have climbed into six figures (typically 1-3% of deal value for mid-market transactions, based on our experience advising business owners through exits). Your management team knows about the sale. And now, sitting across from your advisor, you’re staring at revised terms that bear little resemblance to the LOI you signed with such optimism. The buyer wants a 20% price reduction, an extended earnout, and a two-year employment commitment you never agreed to. Every instinct screams to push through, to salvage something from this exhausting process. But the hardest decision you’ll face isn’t whether to sell. It’s knowing when to walk away from a deal that no longer serves your interests.

Executive Summary

Walk-away decisions represent one of the most difficult tests of seller discipline in M&A transactions. After investing significant time, money, and emotional energy into a deal, business owners face immense pressure to accept deteriorating terms rather than restart the process or abandon the sale entirely. Behavioral economists have documented the sunk cost fallacy extensively: the tendency to continue an endeavor because of previously invested resources rather than future value. M&A negotiations create conditions where this cognitive bias can significantly influence seller decision-making.

In our experience advising business owners through exit processes, we’ve found that sellers who establish clear minimum acceptable terms before negotiations begin tend to report greater confidence in their decisions, whether they ultimately close or walk away. This isn’t because pre-defined thresholds guarantee better economic outcomes (the research on that specific question remains limited), but because they provide a rational anchor when emotions run high.

This article offers a practical framework for evaluating walk-away decisions, identifies warning signs that transactions may be deteriorating, and provides tools for making continuation decisions under pressure. We’ll cover how to establish your walk-away thresholds before entering negotiations, recognize deal degradation patterns, and maintain the discipline to terminate transactions that no longer meet your objectives. We’ll also address when walking away may not be your best option, because the decision to terminate carries real costs that must be weighed against accepting imperfect terms.

A critical caveat before we proceed: This framework assumes you have genuine walk-away alternatives: either other potential buyers, the ability to continue operating profitably, or sufficient financial reserves if the sale doesn’t close. If your situation involves financial distress, limited time, or urgent capital needs, your walk-away thresholds must be adjusted accordingly, and you may not have a meaningful walk-away option at all. Recognizing this reality is necessary before applying any of the guidance that follows.

Introduction

The M&A process creates a peculiar form of tunnel vision. What begins as a strategic decision (should I sell my business?) gradually transforms into an emotional commitment to completing a specific transaction. This shift happens so gradually that most sellers don’t recognize it until they’re deep in due diligence, facing terms they never would have accepted at the outset.

We’ve observed this pattern in our advisory work, though we acknowledge the limitation of drawing conclusions from our own client base. A seller enters negotiations with clear objectives: a certain price, reasonable terms, a clean exit. Months later, they may find themselves rationalizing earnout structures that shift significant risk back to them, non-compete clauses that restrict their future opportunities, and purchase prices that have declined through various “adjustments” discovered in due diligence.

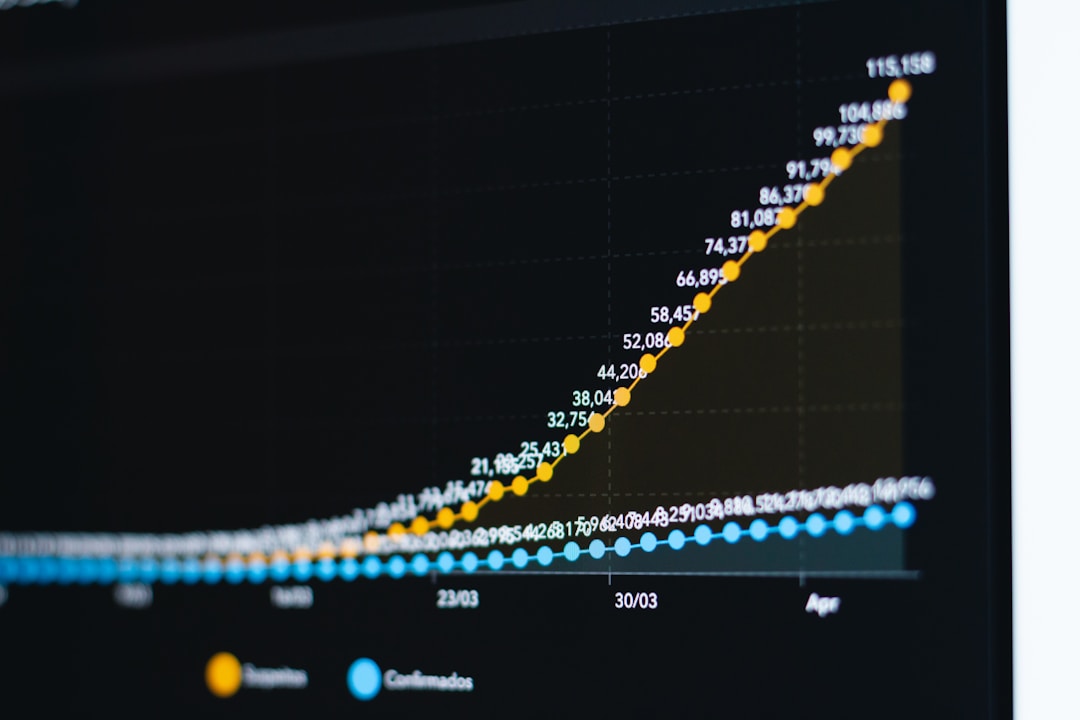

According to M&A market studies, price adjustments between LOI and closing are common, with typical erosion ranging from modest working capital true-ups to more significant reductions depending on due diligence findings. The variance depends heavily on deal size, buyer sophistication, and the thoroughness of the seller’s pre-sale preparation.

The cost of walking away feels enormous because it’s tangible and immediate. You can count the legal fees, quantify the management distraction, and measure the months invested. The cost of accepting a bad deal, by contrast, feels abstract and distant until you’re living with the consequences. However, walking away also carries costs that are often underestimated: potential employee departures if the team loses confidence, customer concerns about business stability, and the expense of reengaging with new buyers.

Walk-away decisions become particularly challenging because they require acknowledging that your initial judgment may have been incomplete. Perhaps you overestimated your leverage, underestimated the buyer’s negotiating sophistication, or simply failed to anticipate how the deal would evolve. Admitting these miscalculations feels uncomfortable, so sellers sometimes double down rather than reconsider.

The most successful exits we’ve witnessed share a common characteristic: sellers who established clear walk-away thresholds before entering serious negotiations and demonstrated the discipline to honor those boundaries when tested, or who recognized when their thresholds needed adjustment based on new information about their alternatives.

Establishing Your Walk-Away Framework Before Negotiations

The time to define your walk-away thresholds is before you sign a letter of intent, not when you’re deep in due diligence facing pressure to compromise. This preemptive framework serves as your anchor when emotions run high and sunk costs loom large.

Defining Your Minimum Acceptable Terms

Your walk-away framework should address four critical dimensions: economic terms, deal structure, post-close obligations, and timeline parameters.

Economic terms go beyond headline purchase price. Consider your minimum acceptable value after accounting for earnouts, working capital adjustments, and holdbacks. If a buyer offers $10 million but $3 million sits in a two-year earnout tied to aggressive targets, your guaranteed proceeds are $7 million. Working capital adjustments can reduce your proceeds by 5-15% depending on industry norms and how your working capital compares to target levels, though this varies significantly based on the seasonality of your business and how “normal” working capital is defined. Ask your advisor what adjustment is typical for your industry, then factor that reduction into your proceeds calculation. Define what economic outcome you need (not hope for, but genuinely require) to justify the transaction.

Deal structure matters as much as price. Will you accept seller financing? How much transaction risk will you retain through representations and warranties? Based on our transaction experience advising mid-market deals, representations typically survive 12-18 months with indemnification caps of 10-15% of purchase price, though smaller deals may have shorter survival periods while larger transactions often extend to 24 months or longer. Expansion beyond these norms (for example, extending survival periods significantly or increasing caps to 20%+ of purchase price) shifts meaningful risk to the seller. Define what structural elements are acceptable before you’re negotiating them under pressure.

Post-close obligations define your life after the sale. Employment agreements, consulting arrangements, non-compete restrictions, and transition assistance requirements all impact your outcome. Strategic buyers typically require 12-36 months of seller retention to ensure knowledge transfer; financial buyers vary more widely. If your exit plan involves immediate retirement or launching a new venture, even a 12-month employment commitment fundamentally changes the transaction’s value to you. Define acceptable parameters: geographic scope (local, state, or national), duration (1-3 years is common; 5+ years is restrictive), and specificity (your specific niche versus entire industry).

Timeline parameters protect against indefinite due diligence. In our experience advising business owners, smaller acquisitions ($2-10 million) typically close within 4-8 months from LOI, while mid-market deals ($10-50 million) often require 6-12 months. However, timeline varies significantly by industry (regulated sectors like healthcare or financial services typically require additional months for approvals) and by buyer type, as strategic acquirers generally move faster than financial buyers requiring external financing. If your deal significantly exceeds these benchmarks without clear justification (such as genuine complexity or regulatory requirements), that may signal problems worth investigating.

The Written Commitment Principle

Document your walk-away thresholds in writing and share them with your advisor before negotiations intensify. This creates accountability and provides an external reference point when pressure mounts. We recommend a simple matrix that specifies your minimum requirements across each dimension, with clear language about which elements are negotiable and which represent hard boundaries.

This written commitment serves another purpose: it forces you to confront your true priorities before emotions cloud your judgment. Many sellers discover, through this exercise, that they haven’t actually thought through what they require. They’ve only imagined what they hope to achieve.

If you lack a professional advisor, consider asking a trusted peer or mentor who has been through an exit to review your thresholds and challenge your assumptions. The goal is external accountability from someone who can provide objectivity when you’ve lost perspective.

Recognizing Deal Degradation Patterns

Transactions rarely collapse suddenly. Instead, they may deteriorate through a series of incremental concessions that, individually, seem manageable but collectively transform an acceptable deal into one that warrants serious reconsideration. Learning to recognize these patterns early provides the opportunity to address them before they accumulate.

The Retrading Pattern

Retrading (renegotiating agreed terms after an LOI is signed) represents a common form of deal degradation. Buyers often justify retrading through findings in due diligence, though experienced acquirers may anticipate certain discoveries and factor them into their negotiating approach.

Warning signs include:

- Purchase price reductions attributed to working capital or quality of earnings adjustments that exceed reasonable industry expectations

- New earnout components introduced to “bridge valuation gaps” that weren’t discussed during LOI negotiations

- Expanded representations and warranties beyond market norms: extending survival from standard 12-18 months to 24+ months, or increasing indemnification caps from 10% to 20%+ of purchase price

- Increased holdbacks or escrow requirements without proportionate justification

- Extended due diligence timelines that repeatedly delay closing

A single adjustment rarely justifies walking away. Most deals involve some negotiation after LOI signing. The pattern to watch for is cumulative erosion: a steady accumulation of concessions that, taken together, fundamentally alter the transaction’s value.

The Control Shift Pattern

Some deals degrade not through economic terms but through the gradual transfer of control from seller to buyer. This pattern manifests when buyers begin acting as if they already own the business before closing.

Watch for demands to approve major decisions, requirements to consult on customer relationships, insistence on participating in key meetings, or pressure to terminate relationships the buyer views unfavorably. These behaviors signal expectations of deference that isn’t yet warranted and may precede more aggressive retrading.

The Timeline Manipulation Pattern

Extended due diligence can benefit buyers in multiple ways. It provides time to uncover additional leverage, increases the seller’s sunk costs and emotional commitment, and creates pressure to close before the seller’s patience expires. When timelines extend without clear justification, careful evaluation is warranted.

Healthy transactions maintain momentum. When weeks pass without meaningful progress, when closing dates are pushed repeatedly, or when due diligence requests expand beyond reasonable scope, you may be witnessing timeline manipulation. However, extended timelines can also reflect legitimate complexity, buyer internal processes, or financing delays. The key is understanding whether the delay serves a purpose or represents a negotiating tactic.

Walk-Away Decision Factors: A Practical Framework

When evaluating whether a deteriorating deal warrants termination, we recommend a structured assessment across five dimensions. This framework helps separate rational analysis from emotional attachment to the transaction, though it should be adapted to your specific circumstances rather than applied mechanically. First-time sellers navigating complex decisions should seek experienced advisory support rather than attempting to use this framework alone.

Factor 1: Economic Threshold Analysis

Compare your current expected proceeds (accounting for all adjustments, earnouts, and contingencies) against your pre-established minimum. This comparison provides signal about whether to reassess, not an automatic decision rule. A meaningful gap warrants careful review; a significant gap warrants serious reconsideration. But your decision depends on your specific alternatives, not the percentage alone.

Calculate your “certainty-adjusted proceeds” by discounting contingent payments based on realistic probability of achievement. Here’s how this works in practice:

Example: Your earnout is $2 million if revenue grows 15% annually. Your historical growth is 5%. In a buyer-controlled environment where you may lack influence over key decisions affecting growth, the probability of achieving 15% growth might realistically be 30-50%. Using a 40% probability estimate: Certainty-adjusted earnout value = $2 million × 40% = $800,000, not the full $2 million.

This calculation doesn’t include the time value of money or the stress and management cost of earnout achievement, both of which represent additional reasons to discount earnout value in your planning.

The appropriate discount depends heavily on context. An earnout targeting maintenance of current performance is more achievable than one targeting aggressive growth. An earnout where you remain as CEO with operational control is more achievable than one where you become a minority voice. Be honest in this assessment. The tendency to overestimate earnout achievement is understandable given sellers’ confidence in their businesses, but buyer-controlled environments introduce variables beyond your control.

Factor 2: Structural Risk Assessment

Evaluate how deal structure has evolved from the original LOI. Create a comparison table documenting original terms versus current terms across key structural elements:

| Element | Original LOI | Current Terms | Assessment Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cash at close | 80% | 65% | Significant reduction in guaranteed proceeds |

| Earnout period | 12 months | 24 months | Extended risk exposure; verify target reasonableness |

| Indemnification cap | 10% of purchase price | 20% of purchase price | Above market norm; negotiate or reconsider |

| Escrow holdback | 5% for 12 months | 15% for 18 months | Substantial capital at risk; understand justification |

| Employment requirement | 6 months consulting | 18 months full-time | Fundamental change to post-exit life; personal decision |

| Non-compete scope | State-level, 2 years | National, 5 years | Highly restrictive; consider future plans |

This visual comparison often reveals cumulative degradation that isn’t apparent when considering each adjustment individually. The goal isn’t to label each change as “acceptable” or “unacceptable” in isolation, but to understand the total picture.

Factor 3: Buyer Behavior Evaluation

How a buyer negotiates can provide insight into potential post-close dynamics, though we should be cautious about overinterpreting. Buyers who retrade aggressively often demonstrate that price and terms remain negotiable from their perspective, which may continue into post-close interactions over earnouts, employment terms, or indemnification claims.

However, negotiating style during deal-making doesn’t perfectly predict partnership behavior. Some aggressive negotiators become reasonable partners once the transaction closes and relationship dynamics shift. Others maintain adversarial approaches. The uncertainty itself is valuable information: consider whether you’re comfortable with this buyer as a partner, because earnouts and employment agreements create exactly that relationship.

If you have serious concerns about the buyer’s character or trustworthiness, evaluate whether your post-close exposure is limited enough to proceed despite those concerns.

Factor 4: Alternative Analysis

Walking away only makes sense if your alternatives are genuinely preferable. Before terminating a transaction, honestly assess your options:

-

Other buyers: Can you approach other buyers, and how does the likely outcome compare to current terms? If you’ve already tested the market extensively, new buyers may not offer significantly better terms.

-

Continued operation: Evaluate whether you can continue operating profitably for 12-18 months while approaching other buyers. If the business is in decline, facing competitive threats, or requires capital you don’t have, continuing to operate may not be realistic.

-

Sale process damage: Has the sale process damaged your business in ways that affect future value? Key employee departures, customer concerns, or management distraction during due diligence can erode value.

-

True costs of walking: Calculate the real cost of walking away, including sunk transaction costs, potential business deterioration, and the expense of approaching new buyers with new due diligence and legal fees.

Before committing to walk away, consider whether specific renegotiation might address your core concerns without terminating entirely. Perhaps you can accept the reduced price if the earnout terms improve, or accept the employment requirement if the non-compete narrows. The choice isn’t always binary.

Sometimes a mediocre deal with a difficult buyer still represents the best available outcome. Use your certainty-adjusted proceeds calculation to compare: Does accepting current terms still exceed your minimum threshold by a meaningful margin? If yes, accepting might be rational even with concerns about the buyer or terms. If no, walking away becomes more defensible (provided your alternatives are genuinely better).

Factor 5: Emotional State Assessment

The most difficult aspect of walk-away decisions involves separating rational analysis from emotional exhaustion. Ask yourself honestly:

- Am I accepting these terms because they meet my objectives, or because I’m tired of negotiating?

- Am I rationalizing concessions to avoid admitting the deal has gone wrong?

- Would I accept these terms if I were starting fresh today with full knowledge of what I now know?

- What would I advise a friend in this identical situation?

Experienced advisors provide value precisely because they can maintain objectivity when sellers have lost perspective. If your advisor recommends walking away but you’re determined to close (or vice versa), that disconnect warrants serious reflection about whose judgment is clearer in the moment.

This framework requires judgment in application. Mechanical adherence to predetermined thresholds without considering changed circumstances can lead to poor decisions in either direction.

The Real Costs of Walking Away

Walking away from a deal carries substantial costs that must be honestly evaluated before making the decision. The article’s guidance on walking away is only useful if you understand what walking actually costs.

Financial Costs

Sunk transaction costs are the most visible: legal fees, accounting work, advisor fees, and management time already invested. For a mid-market deal, based on our experience, this might represent $150,000-$400,000 or more depending on deal complexity and how far into due diligence you’ve progressed.

Future transaction costs are often overlooked. Approaching new buyers means new due diligence, new legal documentation, and potentially new advisor fees. You may spend another $100,000-$300,000 pursuing an alternative.

Business value erosion can be significant. If growth slowed during the sale process, if key employees became distracted or departed, or if customer relationships weakened, your business may be worth less than when you started.

Reputational and Operational Costs

Employee confidence often suffers after a failed exit. Team members who learned about the potential sale may question the business’s stability or start exploring other opportunities. Some may leave.

Customer and vendor perception can shift. If word spread about the potential sale, counterparties may wonder why it failed and what that implies about the business.

Market reputation matters for future transactions. Other potential acquirers may learn the deal failed and question whether problems exist that caused the first buyer to walk.

When Walking Costs More Than Closing

For some sellers, walking away is worse than accepting imperfect terms. This is particularly true when:

- You have no other viable buyers and limited ability to find new ones

- Your business is declining and delays will reduce value further

- You face personal circumstances (health, family, financial needs) that require near-term liquidity

- The gap between current terms and your threshold is modest relative to walking costs

The framework in this article assumes you have genuine alternatives. If you don’t, your “walk-away decision” may actually be a choice between a disappointing deal and a worse outcome. Recognizing this reality (rather than pretending you have leverage you lack) is necessary to making a sound decision.

Making the Walk-Away Decision

Once your framework analysis indicates potential deal termination, the actual decision requires both courage and process. Walking away from a significant transaction is never easy, but doing so strategically can preserve value and create future opportunities when your alternatives genuinely support that choice.

The Pause Before Action

Before announcing termination, pause briefly to ensure your decision is intentional rather than reactive. Use this time to:

- Review your original walk-away thresholds and confirm current terms violate them meaningfully

- Consult with your advisor about alternatives to termination

- Consider whether a final conversation with the buyer might salvage acceptable terms

- Prepare mentally for the buyer’s likely response

Recognize that buyers may not provide unlimited time for deliberation. If facing a deadline, seek advisor input immediately rather than waiting. Sometimes announcing hesitation (rather than termination) creates space for productive renegotiation.

Communicating the Decision

If you determine that walking away is appropriate, communicate clearly and professionally. Avoid burning bridges unnecessarily. Buyers sometimes return with improved terms, and your reputation in the M&A market matters for future transactions.

Frame your communication around objective factors: “The terms have evolved beyond what works for us economically” rather than “Your retrading has been outrageous.” The former preserves the relationship while making your position clear; the latter creates permanent adversaries.

Managing the Aftermath

Walking away from a deal creates both practical and psychological challenges. Your management team may need reassurance about business continuity and their future. Customers and vendors who learned about the potential sale may require communication about stability. Your own processing of the outcome deserves attention.

The business costs of walking away (employee departures, customer concerns, operational disruption) can be substantial. If walking triggers meaningful value erosion, ensure you’ve accurately compared the cost of walking against the cost of accepting the imperfect deal. Sometimes the right answer is accepting terms below your original threshold because your alternatives have genuinely worsened.

Consider a brief period of distance from exit planning before determining next steps. Sometimes the right decision is re-engaging the market with different buyers; sometimes it’s continuing to build the business until conditions improve; sometimes it’s returning to this buyer if they come back with better terms. Allow yourself time to reach this conclusion thoughtfully rather than reactively.

When Walking Away Is the Wrong Decision

This article has focused primarily on recognizing when deals deteriorate and how to evaluate the walk-away decision. But intellectual honesty requires acknowledging that walking away isn’t always the right choice, and that the framework here can be misapplied.

Walking away is likely the wrong decision when:

- Your alternatives are worse than the current terms, even accounting for deal degradation

- You lack the financial runway to continue operating while pursuing other options

- Your business is declining and delay will reduce value further

- The costs of walking (sunk costs plus business deterioration) exceed the gap between current terms and acceptable terms

- Your threshold was set unrealistically high to begin with

A seller who walks away from a $5 million deal expecting better alternatives, only to find no other buyers willing to match that price, may deeply regret the decision. This is why evaluating your alternatives (Factor 4) is critical. Your walk-away decision is only correct if your alternatives are actually better.

Your willingness to walk creates leverage only if the buyer wants the deal more than you do. If this is one of many acquisition targets for them, or if they have no time pressure, your walk-away stance may not move them. Before committing to walk away, assess the buyer’s true motivation and alternatives, not just your own.

Actionable Takeaways

Before entering negotiations:

- Document your minimum acceptable terms across economic, structural, and post-close dimensions

- Share your walk-away thresholds with your advisor in writing, or with a trusted peer if you lack an advisor

- Honestly assess your alternatives and financial runway if the deal doesn’t close

- Commit to reviewing these thresholds at each major negotiation milestone

During due diligence:

- Track all term changes from the original LOI in a comparison document

- Calculate your certainty-adjusted proceeds monthly, discounting contingent payments using realistic probability estimates

- Set timeline expectations appropriate to your deal size, industry complexity, and buyer type

- Monitor for cumulative erosion patterns, not just individual adjustments

When evaluating deteriorating terms:

- Apply the five-factor framework as a structured assessment tool, not as automatic decision rules

- Seek advisor input specifically on walk-away decisions; they provide essential objectivity

- Honestly compare walking costs (including business deterioration) against accepting imperfect terms

- Consider whether targeted renegotiation might address core concerns without terminating entirely

If you decide to walk away:

- Communicate professionally and factually, preserving relationships where possible

- Prepare for the real costs: employee concerns, customer questions, future transaction expenses

- Allow time for processing before immediately pursuing alternatives

- Document lessons learned for future transaction attempts

The discipline to walk away from a bad deal ultimately depends on preparation completed before negotiations intensify and on honest assessment of whether walking truly serves your interests better than closing.

Conclusion

Walk-away decisions test your negotiation discipline and self-awareness in ways few other business decisions do. The sunk cost fallacy pulls toward closing at any price; the fear of restarting pushes toward rationalizing deteriorating terms. Overcoming these psychological forces requires frameworks established before emotions cloud judgment and the wisdom to recognize when those frameworks need adjustment based on new information.

The owners who navigate these decisions successfully understand that their leverage depends on their genuine willingness to terminate discussions, assuming they have viable alternatives. They also understand that walking away carries real costs (financial, operational, and reputational) that must be weighed honestly against accepting imperfect terms.

Your business represents years of work, sacrifice, and achievement. It deserves a transaction that honors that investment, not one that exploits your exhaustion or capitalizes on your sunk costs. But it also deserves clear-eyed analysis of your actual options, not wishful thinking about alternatives that may not materialize.

Sometimes the hardest decision is walking away from a deal that no longer serves your interests. Sometimes it’s accepting terms below your original expectations because your alternatives are genuinely worse. The framework in this article can’t make that decision for you, but it can help ensure you make it with clear eyes and full information.

Walking away isn’t failure. Accepting imperfect terms isn’t failure either. Failure is making either decision without honest analysis of your situation, your alternatives, and the true costs of each path forward.