Specific Performance Rights - Forcing Deal Completion in M&A Transactions

How specific performance clauses enable buyers and sellers to force transaction completion through court orders rather than accepting monetary damages

When a buyer signs your purchase agreement and then gets cold feet three weeks before closing, you face a brutal choice: accept whatever monetary damages you can recover—often a fraction of your company’s value—or fight to force the deal through. Specific performance rights can transform this calculus, giving you the legal tool to compel completion rather than settle for consolation prizes. But these provisions create enforcement opportunities, not guarantees, and as the failed specific performance claims in cases like Hexion v. Huntsman demonstrate, courts retain discretion that can defeat even well-drafted contractual rights.

Executive Summary

Specific performance provisions in M&A purchase agreements represent one of the most powerful and frequently misunderstood protections available to both buyers and sellers. Unlike standard contract remedies that compensate parties with monetary damages when counterparties breach, specific performance rights enable courts to order actual deal completion. For business owners preparing for exit, understanding these provisions can mean the difference between watching your carefully structured transaction collapse and having the legal power to push a committed buyer to close.

This article examines how specific performance clauses function in middle-market M&A transactions, the judicial factors that determine whether courts will actually grant such relief, and the practical limitations that affect enforcement. We look at the specific language formulations that strengthen or weaken these provisions, identify circumstances where specific performance rights provide meaningful protection versus merely theoretical power, and provide frameworks for negotiating remedy provisions including reverse termination fees, escrow arrangements, and security requirements that make enforcement more likely.

For sellers in the $2M-$20M revenue range—a segment where deals are large enough to warrant sophisticated legal structuring but often lack the institutional resources for prolonged litigation—specific performance rights serve as important insurance against buyer walkaway risk. But these provisions work best as negotiating power rather than litigation tools, and sellers must understand both their strength and their substantial limitations.

Introduction

The period between signing a definitive purchase agreement and closing a transaction represents one of the most vulnerable phases of any business sale. Industry practitioners and deal advisors consistently report that a meaningful percentage of announced transactions fail to close, with rates climbing higher during periods of market volatility or economic uncertainty. During the signing-to-closing window—which ranges from 45 days for simpler transactions to 180 days or longer when regulatory approvals are required—market conditions can shift, buyer financing can fail, and acquirer enthusiasm can cool dramatically. Without robust enforcement mechanisms, sellers find themselves holding agreements that buyers treat as optional.

Standard contract law provides monetary damages as the default remedy for breach. In theory, if a buyer abandons a signed deal, the seller can sue for the difference between the agreed purchase price and whatever value they can subsequently obtain. In practice, proving damages in abandoned M&A transactions presents enormous challenges that courts have acknowledged in cases like IBP, Inc. v. Tyson Foods, Inc., 789 A.2d 14 (Del. Ch. 2001). As Vice Chancellor Leo Strine noted in that landmark Delaware decision, determining the fair value of a going concern involves “widely divergent” expert opinions and “inherently imprecise” methodologies. Markets move, businesses continue changing, and establishing what the company would have been worth absent the breach becomes speculative and expensive litigation that can cost $500,000 to several million dollars in legal fees alone.

Specific performance rights offer an alternative path. When properly drafted and appropriately invoked, these provisions enable courts to order breaching parties to actually complete their contractual obligations—to close the transaction as originally agreed. For sellers, this means the potential ability to force buyers to fund acquisitions. For buyers, this means the potential ability to compel sellers to transfer ownership when sellers develop second thoughts.

The availability of specific performance in your purchase agreement fundamentally changes negotiating dynamics, closing behavior, and risk allocation. Understanding how these provisions actually work and their very real limitations enables smarter structuring decisions during the deal process itself.

The Legal Foundation of Specific Performance in M&A

Specific performance exists as an equitable remedy, meaning courts have discretion in granting it rather than applying automatic rules. This discretionary nature creates both opportunity and uncertainty for parties seeking enforcement.

Courts traditionally grant specific performance when three conditions align: the underlying contract is valid and enforceable, monetary damages would be inadequate to compensate the non-breaching party, and the remedy is practically feasible to implement. In M&A transactions, the second factor—inadequacy of monetary damages—typically presents the strongest argument for specific performance.

Most privately held businesses, particularly those with specialized operations or strategic value, are unique. Unlike commodities or publicly traded securities, a privately held company cannot simply be purchased on the open market if a buyer walks away. The strategic fit, synergy potential, and specific characteristics that made the acquisition attractive cannot be replicated with damage payments. Courts recognize this uniqueness, making M&A transactions particularly suitable for specific performance relief.

But judicial discretion means outcomes remain uncertain. Judges consider factors including the behavior of both parties, the practical burden of enforcement, and whether ordering completion serves broader equitable purposes. A seller who has materially breached representations or failed to satisfy closing conditions cannot expect courts to force buyers to close despite those failures.

Jurisdictional Differences That Matter

The legal landscape varies significantly by jurisdiction, and these differences materially affect enforcement outcomes. Sellers should note that regulated industries—including financial services, utilities, and healthcare—may face additional enforcement complexities beyond standard commercial litigation.

Delaware courts, which handle a disproportionate share of M&A disputes because of corporate domicile patterns, have developed the most extensive precedent on specific performance in acquisition contexts. The Court of Chancery has demonstrated willingness to order specific performance in cases like IBP, Inc. v. Tyson Foods, Inc., 789 A.2d 14 (Del. Ch. 2001), where Vice Chancellor Strine ordered Tyson to complete a $3.2 billion acquisition despite Tyson’s claims that IBP had experienced a material adverse effect. Under current Delaware precedent, courts apply a relatively straightforward analysis: if the contract provides for specific performance, the deal represents a unique asset, and the non-breaching party performed its obligations, courts will generally enforce completion.

New York courts take a somewhat narrower approach, requiring more rigorous demonstration that monetary damages would truly be inadequate. New York decisions have emphasized that specific performance remains an extraordinary remedy, and parties must show that the subject matter of the contract is unique in ways that cannot be compensated through money damages. But New York courts have recognized that businesses, particularly in strategic acquisitions, typically satisfy this uniqueness requirement.

California courts apply equitable principles that can be less predictable. California Civil Code Section 3384 provides that specific performance is available when monetary damages would be inadequate, but California courts have shown greater willingness to consider practical difficulties of enforcement and have sometimes declined specific performance when it would create ongoing judicial supervision requirements.

Texas courts generally follow traditional equity principles and have ordered specific performance in business sale contexts, though Texas jurisprudence on M-and-A-specific applications is less developed than Delaware’s.

For middle-market sellers, forum selection clauses designating Delaware as the dispute resolution venue can provide meaningful advantages when specific performance may be necessary.

Drafting Specific Performance Provisions That Actually Work

The language in your purchase agreement determines whether specific performance rights provide genuine protection or merely decorative reassurance. Weak provisions invite challenges; strong provisions create enforceable obligations—though even optimal specific performance provisions face practical limitations based on facts and circumstances.

Effective specific performance clauses contain several critical elements. First, they include explicit acknowledgment that monetary damages would be inadequate—pre-establishing the legal predicate for equitable relief. Second, they contain mutual waiver of any argument that specific performance is inappropriate or unavailable. Third, they specify that parties need not post bond or prove actual damages as preconditions to seeking enforcement.

Consider the difference between weak and strong formulations:

Weak provision: “The parties acknowledge that specific performance may be an appropriate remedy for breach of this Agreement.”

Strong provision: “The parties acknowledge and agree that irreparable damage would occur and that monetary damages would be inadequate compensation in the event of breach of this Agreement. Accordingly, each party shall be entitled to specific performance of the terms hereof, in addition to any other remedy at law or in equity, without the necessity of proving actual damages or posting any bond or other security.”

The strong provision eliminates judicial discretion on the damages inadequacy question, waives bond requirements that could create practical barriers to enforcement, and establishes specific performance as a right rather than a possibility.

Additional strengthening provisions might include forum selection clauses designating courts with favorable specific performance precedent, expedited dispute resolution procedures that prevent drawn-out litigation while the business deteriorates, and explicit statements that time is of the essence regarding closing obligations.

When Specific Performance Rights Actually Protect Sellers

Specific performance rights provide meaningful protection in specific circumstances while offering less value in others. Understanding these distinctions helps sellers focus negotiating effort where it matters most.

The provisions matter most when buyers have clear ability to close but choose not to. Strategic acquirers with strong balance sheets who simply change their minds about acquisition fit, or private equity firms whose investment committees reverse course, can sometimes be compelled to honor commitments when the legal framework supports enforcement. More frequently, robust specific performance rights can serve as negotiating power and, in our experience with well-funded buyers, frequently encourage transaction completion without actual litigation.

The provisions matter less when buyers genuinely cannot close. If acquisition financing falls through and buyers lack alternative funding sources, courts ordering completion accomplishes nothing. You cannot squeeze money from buyers who don’t have it. In these situations, reverse termination fees and financing condition structures matter more than specific performance rights.

How Buyer Type Affects Specific Performance Dynamics

Different buyer categories present distinct specific performance considerations:

Strategic corporate acquirers typically present the strongest specific performance enforcement opportunity. These buyers usually have balance sheet capacity to fund acquisitions and face reputational consequences from abandoned deals. When a strategic acquirer signs a definitive agreement, they generally have board approval and financing commitments in place. Specific performance claims against strategic acquirers carry credible threats because courts can readily order well-capitalized corporations to transfer funds.

Private equity sponsors present more complex dynamics. Fund-level buyers often structure acquisitions through newly formed acquisition subsidiaries with limited assets. Specific performance against an empty shell corporation proves worthless. Sellers should negotiate for fund-level or management company guarantees that provide enforcement targets with actual assets. PE firms may have financing conditions that create contractual walkaway rights, making specific performance unavailable even when the buyer has theoretical capacity.

Family offices and independent sponsors fall somewhere between these categories. They may have substantial assets but less predictable deal behavior than institutional buyers. Specific performance provisions matter here, but security arrangements and reverse termination fees often provide more practical protection.

Search funds and acquisition entrepreneurs typically lack independent resources to fund acquisitions. Specific performance rights against such buyers offer minimal protection; the focus should instead be on earnest money deposits, financing certainty requirements, and personal guarantees from principals.

The Practical Reality of Specific Performance Litigation

While specific performance rights provide valuable contractual protection, sellers must understand the substantial practical challenges that limit enforcement effectiveness.

Time and Cost Considerations

Specific performance litigation typically takes 12 to 24 months from filing to final judgment in standard commercial courts, even when expedited proceedings are available. During this period, the business continues operating under significant uncertainty. Key employees may depart, customer relationships may weaken, and competitive position may erode. Even successful specific performance claims may yield hollow victories if the business has materially deteriorated.

When evaluating whether to pursue specific performance litigation, sellers should consider business deterioration during the litigation period. A framework for this analysis includes:

- Employee turnover impact: Estimate the percentage of key personnel who may depart during an extended period of uncertainty and the associated replacement costs

- Customer uncertainty impact: Calculate potential revenue loss from customers who delay commitments or switch to competitors

- Competitive position erosion: Assess market share loss that may occur while management attention focuses on litigation

- Management distraction: Quantify the opportunity cost of executive time devoted to litigation rather than business operations

Litigation costs compound the challenge. Based on legal industry experience and published legal economics studies, complex commercial litigation frequently costs $1 million to $3 million in legal fees for cases proceeding through trial. For a $10 million transaction, spending $1.5 million on litigation to force closing fundamentally changes the economics.

Some agreements address timing through expedited dispute resolution provisions and preliminary injunction procedures. The Delaware Court of Chancery, recognizing the time-sensitive nature of M&A disputes, has established expedited proceedings that can reach trial within 60 to 90 days. But even expedited Delaware proceedings require substantial legal resources and management attention.

Cases Where Specific Performance Failed

Understanding specific performance failures proves as important as understanding successes:

Hexion Specialty Chemicals, Inc. v. Huntsman Corp., 965 A.2d 715 (Del. Ch. 2008): Despite Huntsman’s claims for specific performance, the Delaware court found that Hexion was not required to close because the combined entity would be insolvent, making specific performance impractical. This case illustrates that financing capacity and solvency considerations can defeat specific performance claims even when buyers technically breached.

In re Nine West Holdings (2020): Post-acquisition disputes illustrated how specific performance limitations in the original deal structure affected subsequent creditor claims. The case demonstrated that specific performance rights must be evaluated in context of overall deal structure.

Consolidated Edison, Inc. v. Northeast Utilities, 426 F.3d 524 (2d Cir. 2005): A buyer successfully avoided specific performance by demonstrating that regulatory conditions—specifically antitrust approval requirements—could not be satisfied. Sellers cannot use specific performance to override legitimate closing conditions.

These cases illustrate that specific performance rights, while valuable, do not guarantee outcomes. Courts maintain equitable discretion that can defeat enforcement even when contractual provisions appear robust.

The Interplay Between Specific Performance and Termination Fees

Purchase agreements typically contain both specific performance provisions and termination fee structures. Understanding how these mechanisms interact proves necessary for proper risk allocation.

Termination fees—payments triggered when defined termination events occur—provide liquidated damages that substitute for uncertain breach litigation. Reverse termination fees, paid by buyers who fail to close, protect sellers against funding failures and buyer walkaway. Forward termination fees, paid by sellers, protect buyers against superior offer acceptance or seller board fiduciary outs.

Based on recent market data from deal terms studies, reverse termination fees in middle-market transactions typically range from 3% to 6% of transaction value. For a $15 million deal, that translates to $450,000 to $900,000—meaningful amounts but far less than the full purchase price. Larger transactions tend toward the lower end of this range, while smaller deals with higher relative execution risk often command fees at the higher end.

Structuring the Fee-Performance Relationship

The relationship between termination fees and specific performance requires careful drafting. Some agreements make termination fees the exclusive remedy, eliminating specific performance rights entirely. Others preserve specific performance as an alternative, allowing non-breaching parties to choose between forcing completion and accepting termination payments.

For sellers, the optimal structure preserves choice. You want the ability to demand specific performance when buyers can close but won’t, while accepting termination fees when buyers genuinely cannot close. Agreement language should explicitly preserve this election rather than making termination fees exclusive.

Consider this framework for evaluating remedy structures:

Exclusive termination fee (buyer-favorable): Buyer pays defined fee and walks away; seller cannot pursue specific performance. This structure caps buyer exposure and provides seller certainty about minimum recovery.

Termination fee plus specific performance election (balanced): Seller chooses between accepting termination fee or pursuing specific performance. This preserves seller optionality while giving buyer clarity on alternative outcomes.

Specific performance primary, termination fee secondary (seller-favorable): Seller first seeks specific performance; termination fee applies only if specific performance proves unavailable. This structure maximizes seller enforcement rights but may face buyer resistance.

Termination fee amounts also affect specific performance dynamics. Higher reverse termination fees reduce buyer walkaway incentives, making specific performance less necessary. Lower fees preserve buyer optionality, making specific performance rights more important as genuine enforcement mechanisms.

Alternative Enforcement Mechanisms

Specific performance represents one tool in a broader enforcement toolkit. Sophisticated sellers consider complementary mechanisms that may provide more practical protection.

Escrow and Security Arrangements

Escrow deposits held at signing provide immediate security that doesn’t require litigation to access. Typical middle-market transactions involve 5% to 10% of purchase price held in escrow pending closing. Unlike specific performance, which requires court action, escrow releases can be structured for automatic or streamlined release upon defined trigger events.

Security requirements should be calibrated to buyer alternatives and process competitiveness. In auction situations, excessive security demands may disadvantage sellers relative to more flexible counterparties. Sellers should assess whether they’re negotiating with a single buyer or running a competitive process before pushing aggressively on security terms.

Parent company guarantees extend enforcement reach beyond acquisition vehicles to entities with actual assets. When private equity sponsors or corporate parents create acquisition subsidiaries, guarantees ensure that specific performance claims and damage awards can be satisfied from well-capitalized guarantors.

Letters of credit from qualified financial institutions provide third-party security independent of buyer financial condition. While less common in middle-market transactions because of cost, letters of credit eliminate counterparty risk concerns.

Financing Condition Structures

How purchase agreements treat acquisition financing significantly affects specific performance availability. Deals conditioned on buyer obtaining financing create contractual walkaway rights when financing fails—making specific performance unavailable because buyer’s closing obligation never became unconditional.

Sellers seeking specific performance protection should negotiate for:

- Financing commitments delivered at signing rather than contingent provisions

- Buyer representations regarding financing availability and commitment quality

- Limited or no financing conditions, with reverse termination fees covering financing failure scenarios

- Marketing period requirements that obligate buyers to pursue financing diligently

Earnest Money and Deposits

Non-refundable deposits—typically 2% to 5% of transaction value—provide immediate compensation upon buyer breach without litigation. Unlike specific performance, deposit forfeiture occurs automatically upon breach, providing seller with liquid funds rather than uncertain court claims.

Deposit structures can include graduated forfeiture based on timing, with higher retention amounts as transactions approach closing. This creates increasing incentives for buyers to perform as their investment in the transaction grows.

Why Middle-Market Sellers Face Distinct Dynamics

The $2M-$20M revenue segment represents a distinct M&A market category where specific performance dynamics differ from both smaller and larger transactions.

Deals in this range are large enough to warrant sophisticated legal structuring—purchase agreements, representation and warranty frameworks, and formal closing conditions. But they typically lack the institutional resources available in larger transactions. Sellers rarely have dedicated M&A counsel on staff, extensive board oversight of transaction processes, or substantial litigation budgets to pursue enforcement actions.

Buyers in this segment span a wide range from strategic acquirers executing tuck-in acquisitions to independent sponsors with complex capital structures to family offices seeking operating businesses. This diversity creates variable counterparty risk that requires transaction-specific assessment.

The combination of meaningful transaction values and limited institutional resources makes contract drafting particularly important. Sellers cannot afford the prolonged litigation that larger companies might sustain, making specific performance provisions valuable primarily as negotiating power rather than practical litigation tools. This reality should inform remedy structure negotiations, emphasizing provisions that provide immediate security (escrow deposits, guarantees) alongside specific performance rights that boost negotiating position.

Calculating What Monetary Damages Miss

Understanding why monetary damages often prove inadequate helps illustrate specific performance’s value proposition.

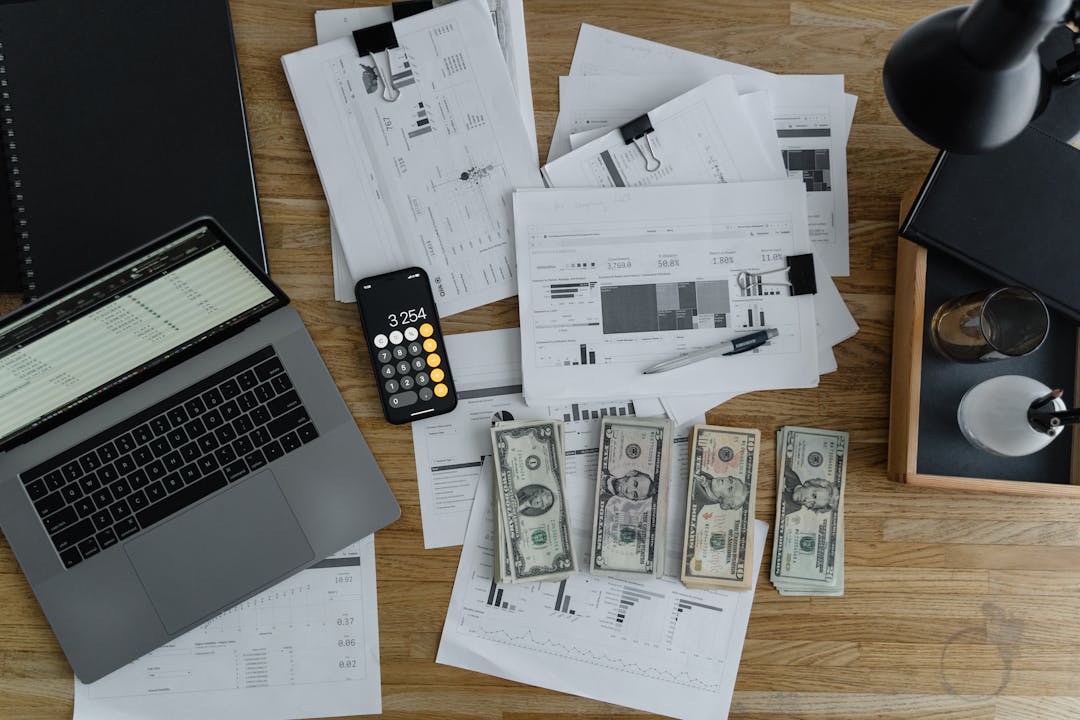

Consider a manufacturing company selling for $12 million to a strategic acquirer. Three weeks before closing, the buyer attempts to walk away citing general market concerns (not a valid material adverse effect under the agreement). What would monetary damages look like?

Direct damages calculation:

- Original purchase price: $12,000,000

- Company fair value after buyer walkaway (damaged reputation, employee uncertainty, customer concerns): $9,500,000 to $11,000,000

- Apparent damages: $1,000,000 to $2,500,000

But the calculation becomes contested:

- Buyer argues market conditions reduced value independent of breach

- Buyer argues seller failed to mitigate damages by not pursuing other acquirers quickly enough

- Buyer argues original price reflected deal-specific synergies not available to other buyers

- Expert valuation opinions diverge by $3 million or more

Litigation costs and timing:

- Legal fees through trial: $800,000 to $1,500,000

- Expert witness fees: $150,000 to $300,000

- Time to resolution: 18 to 36 months

- Present value discount on any recovery

Net recovery range: After litigation costs, expert fees, time value, and uncertainty discount, sellers might net $200,000 to $1,200,000—a fraction of the original transaction value and far less than the apparent damages.

Specific performance, when enforceable, delivers the full $12 million purchase price. Even when specific performance proves unavailable or impractical, credible specific performance claims often produce negotiated settlements substantially exceeding what damages litigation would yield.

Negotiating Framework for Remedy Provisions

Approaching remedy provision negotiations strategically requires understanding your counterparty’s interests and your own risk priorities.

Sellers should prioritize preserving specific performance rights against well-funded buyers, establishing meaningful reverse termination fees as fallback protection, eliminating or limiting financing conditions that create buyer walkout opportunities, and including expedited dispute resolution procedures.

Key negotiating points include resisting any language making termination fees exclusive remedies, ensuring specific performance provisions apply to all material obligations rather than limited subsets, including parent company guarantees when dealing with acquisition subsidiaries, and specifying favorable forum selection for potential disputes.

Buyers typically resist unlimited specific performance exposure and seek defined walkaway options. Finding middle ground might involve higher reverse termination fees in exchange for capped specific performance windows, or financing conditions with clear outside dates that balance buyer flexibility with seller certainty.

Security arrangements improve specific performance practicality. Escrow deposits, letters of credit, or parent guarantees provide assets to satisfy judgments and signal buyer commitment. Sellers should negotiate for meaningful security—typically 5% to 10% of transaction value—held until closing to ensure buyer accountability, while calibrating these requirements to the competitive dynamics of their specific sale process.

Actionable Takeaways

Review specific performance language carefully in any purchase agreement before signing. Ensure provisions explicitly acknowledge damages inadequacy, waive bond requirements, and preserve enforcement rights alongside rather than instead of termination fee remedies.

Assess buyer capacity to close independently of legal enforcement rights. Strong specific performance provisions matter most against well-funded counterparties; they provide little protection against buyers who genuinely cannot fund acquisitions.

Negotiate expedited dispute resolution procedures to reduce the time gap between breach and enforcement. Standard litigation timelines undermine specific performance utility regardless of substantive legal rights.

Insist on meaningful security arrangements—escrow deposits or parent guarantees—that provide practical enforcement mechanisms beyond court orders. Security converts legal rights into accessible assets.

Understand the termination fee interaction and preserve election rights. Optimal structures let sellers choose between forcing completion and accepting termination payments based on actual circumstances at the time of breach.

Consider jurisdiction and forum selection strategically. Delaware courts offer more predictable specific performance precedent than courts with limited M&A experience, and the Court of Chancery’s expedited proceedings can provide resolution in months rather than years.

Recognize that specific performance works best as negotiating power rather than litigation reality. The credible threat of enforcement can encourage settlement or performance; actual enforcement through completed litigation remains expensive and uncertain.

Conclusion

Specific performance rights represent important protection against buyer walkaway risk in M&A transactions, but they are neither foolproof nor self-executing. For sellers in the middle market, where transactions often represent life’s work and retirement security, the ability to credibly threaten forcing committed buyers to actually close provides power that monetary damage claims cannot match.

Yet specific performance is far from magic. Courts retain equitable discretion, litigation takes time and money, and enforcement against incapable buyers accomplishes nothing. These provisions work best as part of wide-ranging remedy structures that include meaningful termination fees, appropriate security arrangements, and careful counterparty due diligence. They provide greatest value against capable buyers who could close but prefer not to, and limited protection against genuinely incapable counterparties regardless of legal rights.

As you approach your exit transaction, treat remedy provisions as core deal terms warranting serious attention—not boilerplate to accept without review. The provisions you negotiate today determine your enforcement options if your buyer attempts to abandon tomorrow. With proper structuring, specific performance rights ensure that signed purchase agreements carry genuine weight: binding commitments backed by credible enforcement mechanisms, not optional letters of intent dressed in formal language. But remember that the goal is closing your deal, not winning litigation, and the best specific performance provision is one that never needs to be invoked because it successfully deterred buyer misbehavior from the start.