The Control Loss Preparation - Psychological Readiness for Ownership Transition

Mental preparation frameworks help business owners navigate the profound shift in authority and agency that comes with selling their company

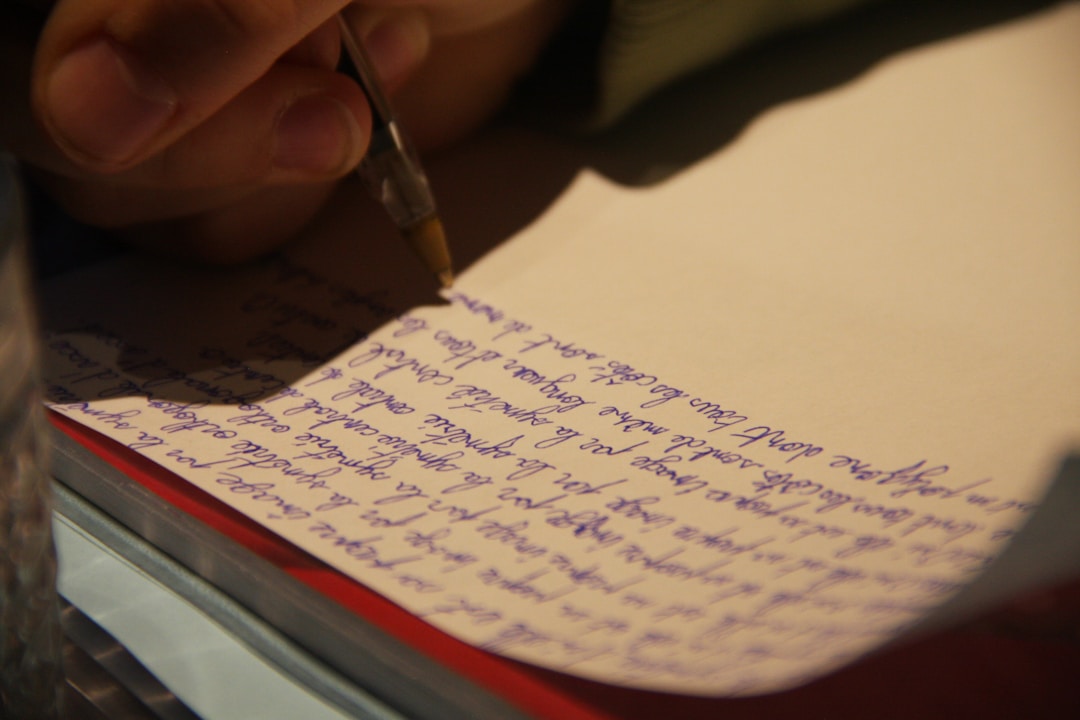

You built this company from nothing. Every major decision for the past fifteen or twenty years has flowed through you: hiring, firing, strategy, pricing, culture, everything. Now imagine walking into that same building, seeing someone else in your office, and having to ask permission to implement an idea you know would work. That moment is coming, and most owners are completely unprepared for how it will feel.

Executive Summary

The psychological impact of losing control during a business sale represents one of the most underestimated challenges in the exit process. While owners spend months preparing financial statements and optimizing operations, few dedicate meaningful time to preparing themselves for the fundamental shift in authority and agency that ownership transition creates.

This control loss preparation affects sellers regardless of their post-close role. Whether you’re walking away entirely, staying on as a consultant, or remaining in a leadership position under new ownership, the dynamic changes forever. You will no longer be the final decision-maker. Your vision will compete with (and often yield to) someone else’s priorities.

The adjustment challenges are significant. In our practice with approximately 300 transactions across fifteen years, we’ve tracked client outcomes and observed that roughly half of business owners in our $2 million to $25 million revenue range report notable dissatisfaction, disorientation, or identity struggles within the first year after selling. Many experience what psychologists call role loss grief: struggling with diminished status, reduced influence, and the absence of daily validation that comes from running your own enterprise. They describe feeling invisible, irrelevant, or frustrated beyond measure.

Important context: This article addresses the psychological dimensions of exit preparation. Equally important are the deal dimensions: price negotiation, earnout structures, representations and warranties, and post-close protections. Psychological preparation without rigorous deal preparation is incomplete. Both are necessary for a successful transition.

The encouraging news: these psychological challenges tend to respond well to advance preparation for many owners. Those who mentally rehearse control transition before the sale, develop new sources of identity and agency, and create structured frameworks for the handover period typically report smoother adjustment than those who assume they’ll figure it out when the time comes (though individual outcomes vary significantly based on personality, financial results, and exit circumstances).

Introduction

Over the past fifteen years, we’ve advised approximately 300 business owners across manufacturing, professional services, and technology sectors with revenues between $2 million and $25 million. A consistent pattern emerges in those transactions: the psychological preparation gap. Owners invest thousands of hours getting their businesses ready to sell: cleaning up financials, documenting processes, building management teams, optimizing profitability. These activities consume years of careful attention.

But when we ask those same owners what they’re doing to prepare themselves for life after the sale, we typically encounter awkward silence. “I’ll figure it out” ranks as the most common response, followed by vague references to golf, grandchildren, or travel. The implicit assumption is that selling the business is the hard part, and everything after that will sort itself out naturally.

This assumption proves wrong for a significant percentage of sellers. Our observation that roughly half experience notable adjustment difficulties aligns with established psychological research on major life transitions. William Bridges’ foundational work on transitions demonstrates that role loss (whether through retirement, career change, or business exit) frequently triggers adjustment difficulties that catch people off guard. Herminia Ibarra’s research on career identity transitions shows that people often underestimate how much of their self-concept is tied to their professional role until that role disappears.

The primary driver of post-exit struggles often isn’t financial. Most sellers in our practice achieve or exceed their monetary goals. The crisis stems from underestimating how profoundly the loss of control affects daily life, compounded in some cases by legitimate business concerns about buyer decisions or earnout outcomes.

Control loss preparation isn’t about becoming comfortable with discomfort or learning to accept less. It’s about understanding what control has actually provided you (identity, structure, purpose, social connection, intellectual stimulation, and validation) and deliberately building alternative sources for these needs before you hand over the keys.

This article examines the control loss dynamics that make ownership transition psychologically challenging, identifies the specific adjustment challenges sellers face, and provides mental preparation frameworks that appear to reduce adjustment difficulty (though they should be viewed as risk reduction rather than risk elimination).

Understanding What Control Actually Provides

Before you can prepare for losing control, you need to understand what control has been giving you. Most owners significantly underestimate how many psychological needs their business satisfies beyond the obvious financial ones.

The Hidden Benefits of Being in Charge

Running your own business provides far more than income. Consider what a typical day delivers to you psychologically:

Identity and Status. When someone asks what you do, you answer with pride. Your role as owner defines you in your community, your industry, and often your family. People treat you with respect (sometimes deference) because of your position. This status accrues automatically, without you having to earn it each day.

Decision Authority. You face problems and you solve them. Nobody second-guesses your choices or requires you to justify your reasoning. The satisfaction of seeing your decisions play out (even when they’re wrong) provides constant intellectual engagement.

Social Structure. Your business forces you out of bed, into conversations, and through your day. The employees, customers, vendors, and advisors you interact with constitute your primary social network, often without you recognizing this dependence. For owners with relationship-intensive businesses or extroverted personalities, this social structure benefit is particularly acute.

Purpose and Meaning. The business needs you. People depend on your judgment, your vision, your energy. This sense of being needed fuels motivation in ways that pure leisure cannot replicate.

Validation and Feedback. Every sale, every satisfied customer, every profitable quarter confirms that you’re competent, that your efforts matter. This constant feedback loop becomes deeply ingrained.

When you close the sale, your formal control disappears abruptly. But the psychological benefits can be partly preserved through structured withdrawal pre-close and, for some owners, through carefully designed post-sale roles. The risk is losing them all at once without preparation. Advance preparation (the topic of this article) allows you to manage this transition rather than experiencing it as sudden.

Why “I’ll Stay Involved” Rarely Solves the Problem

Many sellers (though certainly not all) negotiate post-close roles precisely because they recognize, at some level, that walking away entirely feels terrifying. They’ll serve as consultants, remain as executives, or join the board. These arrangements seem to offer the best of both worlds: liquidity plus continuity.

In our experience, hybrid arrangements frequently complicate the psychological transition rather than ease it, because you’re present for decisions but not making them. You watch strategies unfold that you would have handled differently. The new owners tolerate your input because the deal requires it, not because they value your perspective.

Worse, the role perpetuates your attachment to your old identity while preventing you from building a new one. You’re trapped in an unsatisfying middle ground: too involved to move on, too sidelined to feel fulfilled.

But carefully structured transition roles, with clear boundaries and defined exit timing, can provide a gentler adjustment path. The difference lies in design. This isn’t an argument against transition roles. Structured handover periods benefit buyers and sellers alike when designed properly. But sellers who view these arrangements as psychological solutions rather than business necessities typically end up disappointed.

The Control Loss Dynamics That Destabilize Sellers

Understanding the specific psychological mechanisms that make control loss difficult helps you anticipate and prepare for them. These dynamics operate below conscious awareness, which makes them particularly disruptive. The intensity varies significantly based on personality type, business model, and planned post-exit involvement.

The Agency Collapse

For decades, you’ve operated with near-complete agency. Something bothered you, you fixed it. You spotted an opportunity, you pursued it. This constant cycle of perception-decision-action defines the entrepreneurial experience.

After selling, this cycle breaks. You still perceive problems and opportunities (your pattern recognition doesn’t disappear) but you can no longer act. The gap between seeing what should happen and being unable to make it happen creates profound frustration for many sellers.

Many sellers, particularly those whose identity is built on entrepreneurial decision-making, experience this agency collapse acutely. They see mistakes being made, strategies failing, culture eroding, but they’re contractually, practically, or socially prohibited from intervening. The agency they took for granted reveals itself as the foundation of their psychological equilibrium. Other sellers, though, experience the loss of constant decision-making as relief rather than deprivation. They’ve become tired of the responsibility.

The Relevance Vacuum

When you ran the business, people sought your opinion constantly. Your phone buzzed with questions. Meetings couldn’t start without you. Decisions waited on your judgment.

After the sale, the phone goes quiet. The meetings happen without you. Decisions get made by people who never think to ask your perspective. You’ve become institutionally irrelevant.

This relevance vacuum hits extroverted owners particularly hard. Their energy came from constant interaction, from being at the center of organizational activity. Without that stimulation, they experience something resembling withdrawal: restless, irritable, understimulated. Introverted owners, by contrast, may experience relief rather than loss. The challenge for them often lies elsewhere, in finding new sources of meaning and purpose rather than missing the social stimulation.

The Authority Inversion

Perhaps no dynamic creates more difficulty than the authority inversion experienced by sellers who remain involved post-close. Yesterday, your word was final. Today, you report to someone else.

The authority inversion requires psychological flexibility that many entrepreneurs lack. Building a company demands conviction, persistence, and a certain stubbornness about your vision. These traits, needed for success as an owner, become liabilities when you’re no longer in charge. The same persistence that built the company now manifests as resistance to new leadership.

The Validation Deficit

Running a business provides constant validation. Customers buy from you, confirming your product has value. Employees show up each day, confirming you’ve created something worth being part of. The bank account grows, confirming your decisions were sound.

After selling, these validation sources change. Leisure, golf, and travel provide different forms of validation (competence in sport, experiences shared with family, mastery of new skills) but they’re rarely as immediately gratifying as business metrics. Building new validation sources that feel substantive is part of the preparation work. The validation deficit leaves many sellers feeling uncertain about their value in ways they haven’t experienced since their early career.

Mental Preparation Frameworks for Reduced Authority

The control loss dynamics described above tend to respond well to advance preparation for many owners. Those who spend time before the sale building psychological resilience typically report smoother transitions (though individual variation is substantial, preparation doesn’t guarantee easy adjustment, and multiple factors beyond preparation influence outcomes). Here are frameworks we’ve seen help.

The Identity Diversification Project

Most owners arrive at exit with concentrated identities. When 60 to 80 percent of your self-concept connects to your business owner role, losing that role can devastate you psychologically. The higher that concentration, the more acute the post-exit crisis tends to be.

Begin this work three to five years before you think you might exit (though these timelines represent ideal preparation scenarios). Market conditions, health changes, or exceptional opportunities may warrant shorter preparation periods with acceptance of increased adjustment challenges. The key is that identity sources must be real, not hastily assembled. You’re not finding hobbies; you’re building alternative sources of meaning and impact.

Important cost consideration: This identity diversification requires significant time investment. Expect 10-15 hours weekly for identity development activities across board service, mentoring, community involvement, and relationship building. Some owners worry that reducing business focus during preparation might impact performance, though in practice this concern proves overblown when the transition is gradual.

Here’s an example of how identity concentration might look for a typical owner, and how it might be rebalanced:

| Domain | Current Investment | Target Investment | Specific Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business Owner | 70-80% | 15-25% | Delegate progressively, reduce daily involvement |

| Family Member | 10% | 25% | Deepen relationships, create new traditions, be present |

| Community Member | 5% | 20% | Join boards, volunteer meaningfully, build local impact |

| Mentor/Teacher | 3% | 15% | Advise younger entrepreneurs formally, teach courses |

| Hobbyist/Athlete | 2% | 15% | Pursue mastery in chosen activities, join communities |

The specific percentages matter less than the concept: you need multiple sources of identity so that losing one doesn’t collapse your entire self-concept.

Common failure modes: This approach carries risks including superficial engagement that provides no psychological benefit and over-commitment that increases rather than reduces stress. To mitigate, focus on genuine interest alignment and start with limited commitments before expanding. Some owners treat new activities as boxes to check rather than genuine sources of meaning. This defeats the purpose entirely.

The Control Inventory Exercise

This exercise helps you understand exactly what you’ll lose and plan replacements for each element. Dedicate two 2-hour blocks per week for three weeks. Use a simple log: each time you make a decision, note the category and the domain where you’ll need a replacement post-exit. You don’t need perfect capture; you’re building awareness, not conducting a census.

Categories typically include:

- Strategic decisions (direction, investments, partnerships)

- Operational decisions (processes, systems, vendors)

- People decisions (hiring, firing, promotions, compensation)

- Financial decisions (pricing, spending, capital allocation)

- Validation moments (praise, recognition, successful outcomes)

The specific categories that matter most depend on your business type and personality. If you led primarily through relationships (sales, service, team-dependent operations) focus particularly on the social structure and validation categories.

For each category, identify alternative sources. Where else can you make strategic decisions? Perhaps through nonprofit board service or angel investing. Where else can you make people decisions? Perhaps through mentorship programs or advisory roles with emerging companies.

The goal isn’t to perfectly replicate your current control. That’s impossible. The goal is making sure you have meaningful alternatives for your core psychological needs.

Implementation reality: Many owners find this exercise more challenging than expected. Consider completing it with a transition coach or trusted advisor who can help maintain focus and identify blind spots.

The Scenario Rehearsal Practice

Athletes visualize performance before competition. Musicians mentally rehearse before concerts. But business owners rarely practice for the psychological challenges of transition.

Begin with weekly sessions for the first three months to establish the practice, then move to monthly maintenance sessions. For each session, select one scenario and spend ten minutes writing a description of the situation. Then spend twenty minutes writing your response (what you’d say, what you’d feel, how you’d process it). Finally, spend twenty minutes actually imagining the scenario as vividly as possible, as if it’s happening now. Let yourself feel the emotions. This embodied rehearsal, repeated across multiple scenarios, builds more genuine preparation than intellectual understanding alone.

Note on emotional engagement: Scenario rehearsal requires genuine emotional engagement with difficult situations. Owners who process intellectually rather than emotionally may need professional guidance to make this practice effective. If you find yourself analyzing scenarios without feeling them, consider working with a transition coach who can help you go deeper.

Effective scenarios include:

You’re in a meeting where the new CEO announces a strategy you fundamentally disagree with. How do you respond? What do you say? What do you feel? How do you process the frustration afterward?

A longtime employee calls to complain about changes under new ownership. They want you to intervene. What do you tell them? How do you maintain appropriate boundaries while honoring the relationship?

Six months post-close, you realize the new owners are making a mistake that will damage the business significantly. You’ve raised the concern and been dismissed. What do you do with that knowledge? How do you let go?

At a social event, someone asks about “your company” and you have to explain you sold it. How do you describe yourself now? What’s your new answer to “what do you do?”

The Structured Withdrawal Protocol

Abrupt endings create trauma. Gradual transitions allow adjustment. The structured withdrawal protocol applies this principle to business exit.

Important timeline context: In our experience, exits typically take twelve to twenty-four months from initial decision to close, with significant variation based on deal complexity and market conditions. Plan for a longer runway than you expect. Begin identity diversification three to five years before you think you might exit, to build flexibility.

Critical caveat: This withdrawal approach assumes stable business performance and market conditions. In competitive or declining situations, maintain full engagement until sale completion, accepting that psychological adjustment may be more challenging. Do not reduce involvement if doing so could harm business value.

Rather than maintaining full involvement until closing day and then disappearing, design a progressive reduction in your engagement. This might look like:

Months 18-12 before close: Delegate one major responsibility area. Stop attending meetings in that domain. Let others succeed or fail without your intervention.

Months 12-9 before close: Delegate a second major area. Begin reducing your office presence to four days per week.

Months 9-6 before close: Transfer remaining strategic authority to your successor team. Reduce presence to three days per week.

Months 6-3 before close: Serve primarily in advisory capacity. Office presence two days or less.

Months 3-0 before close: Minimal involvement, focused on deal completion and knowledge transfer.

This gradual withdrawal accomplishes two things. Practically, it prepares the organization to function without you. Psychologically, it allows you to experience control loss in manageable doses rather than all at once. Note that if your purchase agreement requires twelve to twenty-four months of post-close involvement, factor that into your planning: your psychological transition extends beyond the closing date.

The Clean Break Alternative

These frameworks assume you’ll have some ongoing relationship with the business post-sale, whether as a consultant, advisor, or executive. Some founders, though, find that psychological recovery is faster with complete separation.

When clean break may be superior: This option often works better for owners experiencing burnout, those resentful of the business after years of sacrifice, or those genuinely unable to imagine accepting reduced authority. If watching someone else run your company would cause more pain than walking away entirely, a clean break deserves serious consideration.

When clean break may be inferior: Complete separation typically means sacrificing earnout upside tied to performance targets, may leave valuable institutional knowledge untransferred, and eliminates the gradual adjustment period that helps some owners.

The tradeoff: Immediate psychological separation versus potential financial opportunity and smoother buyer transition. Neither approach is universally superior. The right choice depends on your personality, financial situation, and emotional relationship with the business.

This requires different preparation (building external identity sources, creating complete financial independence, establishing new social networks entirely separate from the business) but may be preferable for certain personality types and situations.

Actionable Takeaways

Preparing for control loss requires concrete action, not just intellectual understanding. These frameworks require meaningful ongoing investment: roughly equivalent to 10-15 hours weekly plus direct costs of $25,000 to $50,000 over several years when you account for coaching, training, networking, and professional development. Here’s how to apply them:

Start the identity diversification project now. Don’t wait until you have a signed letter of intent. Begin building alternative identity sources today. Join one meaningful board or advisory role in the next 90 days. Deepen one personal relationship that’s atrophied while you focused on business.

Complete the control inventory exercise. Spend three weeks actively tracking where you exercise control and receive validation. The awareness itself begins the preparation process. Consider working with a coach to avoid blind spots.

Schedule scenario rehearsal sessions. Begin with weekly one-hour blocks for three months to establish the practice, then shift to monthly maintenance. This practice feels awkward but builds genuine resilience.

Design your structured withdrawal protocol. Map out how you’ll progressively reduce involvement over the twelve to twenty-four months before exit, plus any required post-close involvement. Share this plan with your leadership team so they can assume responsibilities appropriately. Make sure your business is stable enough to permit this reduced involvement.

Build a post-exit support system. Identify other sellers who’ve navigated this transition successfully. Their perspective and support during your adjustment period will prove invaluable.

Consider professional support. Look for transition coaches with specific experience in founder exits (not just executive transitions), psychologists licensed in your state with experience in identity transitions, or peer groups of other exiting founders through organizations like YPO, EO, or local angel networks. Based on executive coaching market rates of $200-500 per hour, expect to invest $5,000 to $15,000 in coaching alone over one to two years, with additional costs for training, assessment tools, and group programs.

Don’t neglect deal preparation. Remember that psychological preparation is one dimension of exit readiness. Simultaneously invest in deal structure, earnout protections, representations and warranties insurance, and thorough due diligence. Both dimensions are needed.

Conclusion

The control loss preparation represents important work for every business owner contemplating exit. The psychological challenges of ownership transition are significant and, based on our experience with approximately 300 transactions across manufacturing, professional services, and technology sectors, remarkably common. But they tend to respond to advance preparation for many owners.

But most owners neglect this preparation entirely. They assume their success in building a business will translate automatically to success in leaving it. They believe they’ll adapt naturally to reduced authority, that they’ll find new sources of purpose and validation without deliberate effort.

This assumption fails more often than it succeeds. In our experience, sellers who invest in psychological preparation tend to experience better post-exit adjustment, though individual outcomes vary significantly and multiple factors (including sale price, buyer quality, family situation, and health) also influence whether sellers thrive after exit.

The frameworks in this article provide a starting point: diversifying your identity, inventorying your control sources, rehearsing difficult scenarios, and withdrawing gradually rather than abruptly. None of this preparation is particularly complicated. But it does require intention, effort, and the willingness to confront uncomfortable realities about what your business has been providing you psychologically.

View this preparation as risk reduction rather than outcome guarantee. While these frameworks appear to improve adjustment likelihood for owners with sufficient preparation time who are open to gradual transition approaches, post-exit challenges remain common even with advance work. Preparation reduces the probability and intensity of adjustment difficulties; it doesn’t eliminate them.

If you struggle post-exit despite your preparation work, that’s not failure. It’s the reality that psychological reorientation is inherently challenging, and professional support might speed your recovery.

Start this work now. Your future self, navigating the strange new world of post-exit life, will be grateful that you did.